This Week in Native American News (3/23/18): stereotypes, fake art, and Disney

March 23, 2018

Great People Doing Great Things: Battling Stereotypes

“I come from a long line of people who have documented our time and our community,” Ahtone said. “My work is a continuation of their work. I’m not idealistic enough to think that I can change the world, but I know I’ll be doing my part if I keep doing what I do and help others do a better job in covering Indian Country.” Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

When the news about the protest at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation against the Dakota Access Pipeline burst into the spotlight in 2016, Tristan Ahtone welcomed the chance for greater coverage of Native American issues.

But soon Ahtone, a journalist and a member of the Kiowa tribe of Oklahoma, grew dismayed at the way the media handled the stories about the first major indigenous protest since the 1973 Wounded Knee incident in South Dakota.

Most media outlets, even the leading ones, Ahtone said, sidelined the central issues of tribal rights and the government’s responsibility in the Dakota pipeline dispute, and instead replicated old stereotypes by typecasting the protesters as warriors, victims, or magical creatures.

A prize-winning journalist who has worked for “The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer,” National Public Radio, and Al Jazeera America, Ahtone is at work on a set of guidelines for fair and accurate coverage of Native American lives and stories, as part of his stint at Harvard as a Nieman Fellow. The Nieman Foundation chooses 24 journalists from around the world to come to Harvard for a year of academic study.

Ahtone’s guidelines will be based on an internal manual that he developed as head of the tribal affairs desk at High Country News in Colorado, his last post before coming to Harvard, to help reporters avoid clichés, stereotypes, and racially insensitive terms when covering Indian lands and culture.

Read the Full Story Here

How investigators used invisible ink to uncover art fraud

A piece of jewelry advertised on the Facebook page for Al Zuni Global Jewelry Wholesale, which stands accused of manufacturing counterfeit Native American goods in the Philippines to import and illegally sell in the US. Photo courtesy of Al Zuni Global Jewelry Wholesale.

Law enforcement is finally cracking down on the scourge of counterfeit Native American jewelry, which has run rampant in the Southwest for decades. A watershed moment is set to arrive on March 27, with the sentencing of Albuquerque jewelry dealer Nael Ali, who has pleaded guilty to fraudulently selling “Native American” jewelry made in the Philippines.

“Our arts and crafts give us a really concrete way to stay connected to our culture and our history,” Navajo jeweler Liz Wallace told National Geographic. “All this fake stuff feels like a very deep personal attack.” Counterfeits also threaten Native craftspeople’s livelihoods with cheap, sweatshop goods that price out handmade originals. It’s an illegal industry that has gone largely unchecked—until now.

Read the Full Story Here

The Moana Effect: Finding Authenticity at Disney

The storytelling begins when you walk into Aulani's open-air lobby and are greeted not just with a flower lei but by a striking 200-foot mural painted by Hawaiian artist Martin Charlot, one of more than 80 local artists whose work is displayed across the resort.

A surefire way to get some odd looks from your friends is to tell them you're heading to a Disney resort to learn about authentic Hawaiian culture.

But at Aulani, Disney's resort on Oahu's western shore, between breakfast with Minnie Mouse, Instagram-worthy shave ice topped with Mickey ears, and selfies with Moana, guests will find themselves immersed in unexpected details that paint a picture of what it means to be Hawaiian.

"We have this measure of creativity where we're always, like Walt Disney, looking for the next storytelling opportunity and how we might bring a different facet of the story to life, to shine that light on a perspective of Hawaiian culture that has been unexplored by the grander audience of the world," says Kahulu De Santos, Aulani's cultural advisor. "The story that we have is a rich one. But it's not Disney's story - the culture is held by the Hawaiian people."

Read the Full Story Here

How culture shapes your view of the natural world

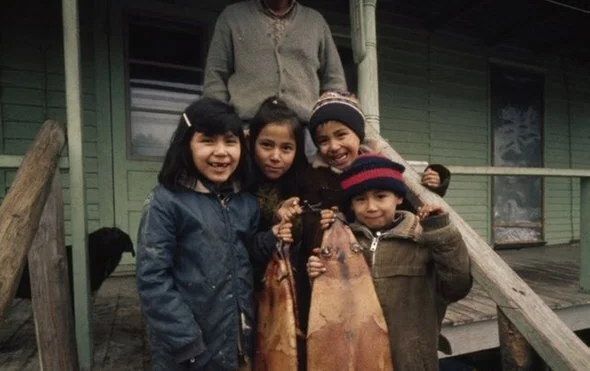

Children of the Menominee Nation in Wisconsin in 2008. Credit: Steven L. Raymer Getty Images

How do young children understand the natural world? Most research into this question has focused on urban, white, middle-class American children living near large universities. Even when psychologists include kids from other communities, too often they use experimental procedures originally developed for urban children. Now researchers have developed a methodology for studying rural Native American kids' perspectives on nature and have compared their responses with those of their city-dwelling peers. The findings offer some rare cross-cultural insight into early childhood environmental education.

Sandra Waxman, a developmental psychologist at Northwestern University, and her colleagues have long collaborated with the Menominee, a Native American nation in Wisconsin. When the researchers presented plans for their study to tribe members who were trained research assistants, the assistants protested that the experiment—which involved watching children play with toy animals—was not culturally appropriate. It does not make sense to the Menominee to think of animals as divorced from their ecological contexts, Waxman says.

Instead one of the Menominee researchers constructed a diorama that included realistic trees, grass and rocks, as well as the original toy animals. The researchers watched as three groups of four-year-olds played with the diorama: rural Menominee, as well as Native Americans and other Americans living in Chicago and its suburbs.

All three groups were more likely to enact realistic scenarios with the toy animals than imaginary scenarios. But both groups of Native American kids were more likely to imagine they were the animals rather than give the animals human attributes. And the rural Menominee were especially talkative during the experiment, contrary to previous research that characterized these children as less verbal than their non–Native American peers. The results were published last November in the Journal of Cognition and Development.

Read the Full Story Here

It's hard to fit so much news in such a small space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!