This Week in Native American News (5/18/18): Changing languages, Building Tiny Houses, and Curing Hepatitis C

May 18, 2018

To Save Their Language, They are Changing It

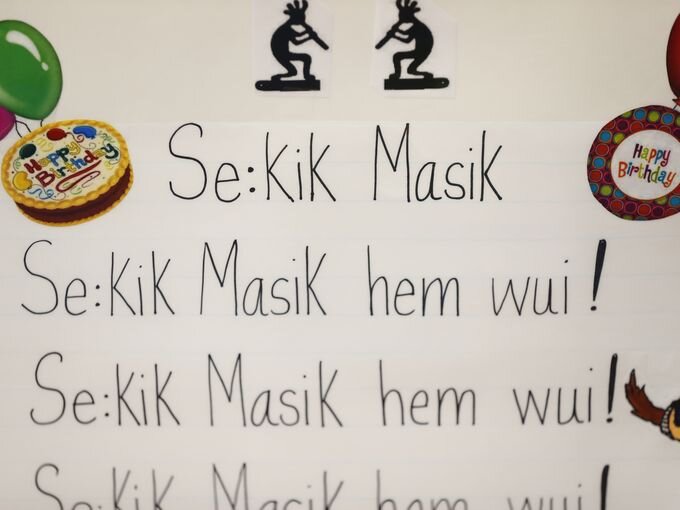

anguage adorns the wall of a cultural classroom at Salt River Elementary School on the Salt River Reservation near Scottsdale Arizona. Photo credit: Patrick Breen/The Republic

Once a month, the elders of Salt River gather to nudge their dying language deeper into the modern world.

Their attempts to save Akimel O'odham from a world overtaken by English had shown few results and produced even fewer fluent speakers. So some of the last speakers started over, diving into the details of their mother tongue to make it simpler to learn.

They picked a new alphabet, re-spelled old words and designed new ones their people had never needed: What, they ask, should be the O’odham word for Christmas tree? For cellphone? Bathroom?

And how could they pass their language on, before the last generation of speakers dies out?

“They’re not trying to change it,” said Raina Thomas, a member of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community who works in the Culture and Language Department. “They’re just trying to name things that didn’t exist in the first place.”

Read the Full Story Here

Indigenous Women Built These Tiny Houses to Block a Pipeline—and Reclaim Nomadic Traditions

Mayuk (left) and Kanahus Manuel (right), founders of the Tiny House Warriors, in front of a completed tiny house on the Neskolinth Reserve outside of Kamloops, British Columbia. Photos by Janice Cantieri

Tiny houses are a trendy way to live minimally and downsize—but for a First Nations community in British Columbia, they’re an act of resistance.

Since the fall, indigenous women of the Secwepemc Nation—calling themselves the Tiny House Warriors—have been constructing tiny houses that they plan to strategically place in the pathway of the proposed Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

These tiny homes have the potential to have a big impact for Secwepemc communities. The houses are being used as symbols of resistance, and they’re also providing something more tangible: affordable, efficient housing that could revitalize Secwepemc nomadic lifeways.

The houses are solar-powered, fitted with composting toilets and wood-burning stoves, and are completely fossil fuel- free. And they’re on wheels. According to Kanahus, the small, moveable houses are also bringing back elements of the Secwepemc’s nomadic hunter-gatherer culture.

Read the Full Story Here

Cherokee Nation Lauded for Hepatitis C Elimination Effort

Recovering addict Judith Anderson figures if she hadn't entered a program that caught and treated the hepatitis C she contracted after years of intravenous drug use, she wouldn't be alive to convince others to get checked out.

The 74-year-old resident of Sallisaw, Oklahoma — about 160 miles (257 kilometers) east of Oklahoma City near the Arkansas border — said the potentially fatal liver disease sapped her of energy and "any desire to go anywhere or do anything."

"It was like living with a death sentence," she said of the infection that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in 2016 killed more people than HIV and tuberculosis combined. "You're just tired all the time."

But things changed for Anderson, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, because she took advantage of the tribe's aggressive program to test for and treat hepatitis C. Federal officials say it could serve as a national model in the fight against the infection.

Read the Full Story Here

Your Weekly History Lesson:

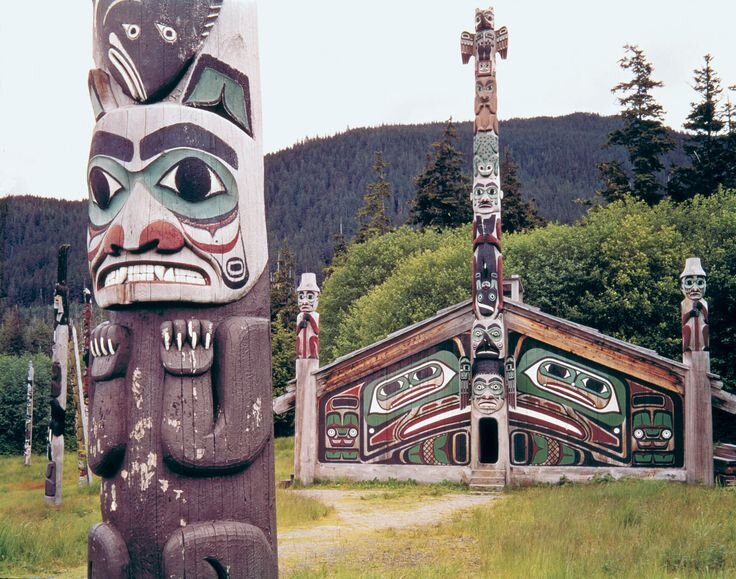

Tlingits Had Totems Near Their Doors

In April 1877, sometime-poet Lieutenant Charles Erskine Scott Wood arrived in Sitka, Alaska, on orders to escort Charles Taylor. The Tlingits were unlike anything American mainlanders had ever encountered. They were a sea people, with a society more similar to the Polynesians of the South Pacific than Indians on the North American continent. Tlingit ancestors settled the ice-free islands of what became southeast Alaska. The sea teemed with life, providing salmon, halibut and shellfish. The rain forest provided trees for gigantic canoes for ocean travel.

While putting the Taylor expedition together, Wood became fascinated with totem poles, some ranging to heights of more than 100 feet. Every important Tlingit house had one near the front door warding off evil spirits and giving an account of family lineage.

The indigenous peoples of Interior Alaska

For the Athabascan people, who have inhabited Interior Alaska for at least 6,000 years, the birch bark canoe was tantamount to today’s pickup truck. Birch bark canoes helped Athabascans survive in some of the harshest conditions on Earth.

The story of the birch bark canoe and many more stories aimed at sharing traditional knowledge have been passed down through generations of the Athabascan people, who make up the largest group of indigenous people in North America, according to the Alaska Native Knowledge Network.

About 800 to 1,000 years ago, Athabascans migrated from Alaska into Canada and as far south as Arizona and New Mexico, but the most ancient core group of Athabascan people lived in Alaska, according to Ben Potter, anthropologist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

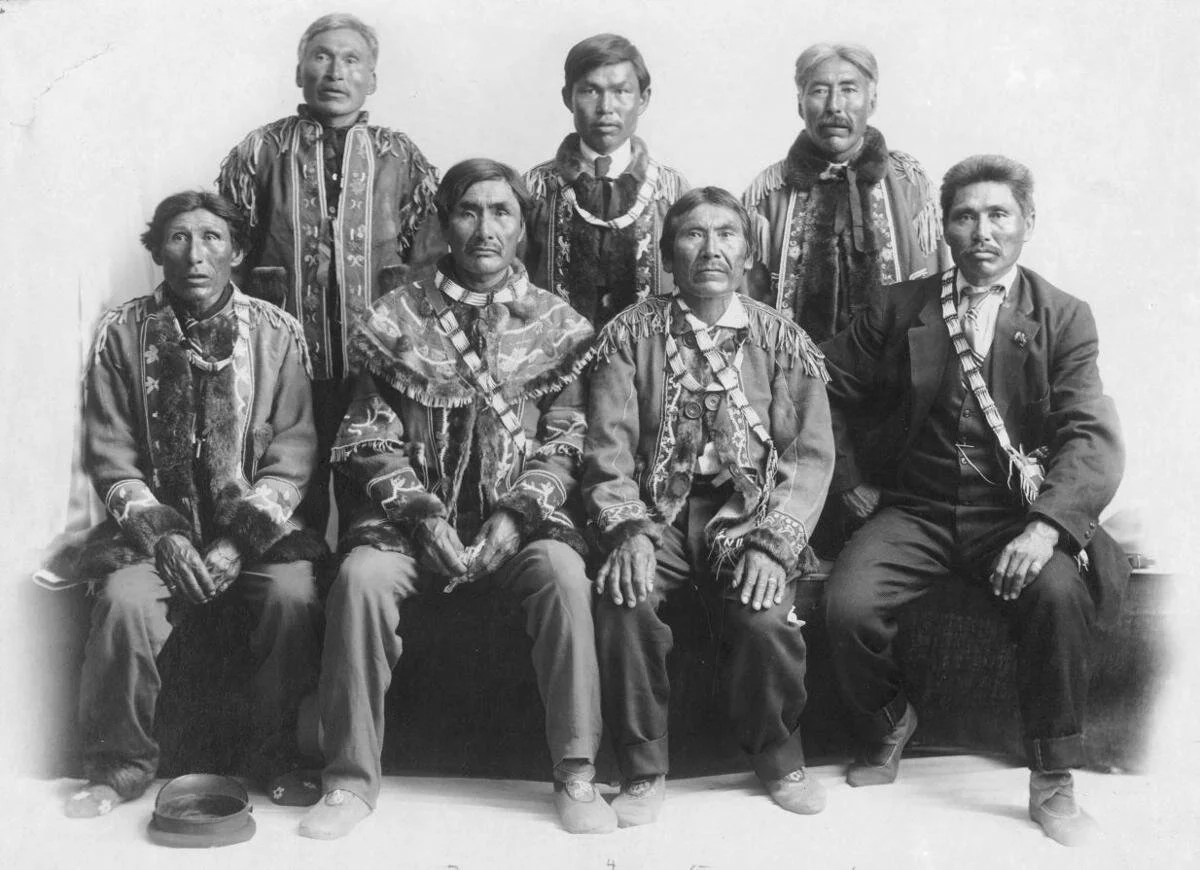

A Rare Collection of 19th-Century Photographs of Native Americans Goes Online

Between 1879 and 1902, a man named John N. Choate served as official photographer for the Carlisle Indian School, a federally-funded boarding school in Pennsylvania established to assimilate Native American children into Euro-American culture. Enrollment of indigenous youth was essentially a way to “civilize” them; the pithy motto of its founder, General Richard Henry Pratt, was “Kill the Indian, and save the man.” Choate, who was non-Native, often documented how students changed over as they received new haircuts and attire and shed aspects of their own culture.

Comprising 225 images, the collection is a small but significant online resource focused on encounters between settlers and indigenous peoples as captured in photography’s early days. These meetings are largely implicit, rather than recorded on paper: white men were the ones behind the large-format cameras, shooting Native subjects, from formal studio portraits to stereographs of them in their homes.

Watch this: Native America on PBS

Gary Glassman, executive producer of PBS’ upcoming docuseries Native America, makes it crystal clear that this project is unlike many programs produced about Native Americans.

“This is not your forefathers’ vision of ancient America,” he tells realscreen. “This is a new vision of the Americas and the people who made it.”

Read more about it here and watch the preview below.

It's hard to fit so much news in such a small space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!