This Week in Native American News (1/3/2020): A new federally recognized tribe, what to do after the women are found, the Native Vice-President, and baby Yoda

January 3, 2020 - Happy New Year!

The Little Shell Tribe of Montana Just Got Federal Recognition.

Five generations of Little Shell people lived and died as members of an American Indian tribe that, according to the federal government, didn’t exist.

Gerald Gray, 52, represents the sixth generation to carry on the fight. Last week, the current chairman of the tribal council was at his office in Billings, Montana when Congress finally approved the Little Shell of Chippewa Indians Tribal Restoration Act, a bill granting federal recognition to the Montana tribe of more than 5,000 people. Gray’s mind was with those who came before him.

“Every morning I smudge and say my morning prayers to my relations because I think they still guide the Little Shell people, ” he said. “I think of my grandfather Ernest Gray who was sent to boarding school as a little boy to remove the Indian from the Indian. They wanted to teach him the white man's ways.”

Now, after more than a century of struggle that began with a controversial treaty agreement in 1892, current and future generations of Little Shell people will be recognized as citizens of a sovereign indigenous nation, the 574th tribe to be recognized by the United States. The tribe will be permitted to exercise limited self-governance through its tribal council. Enrolled citizens will also be able to access federal funding for healthcare, education, and economic development which the U.S. is legally obligated to provide as compensation for appropriating their ancestral land and resources.

Read the Full Story Here

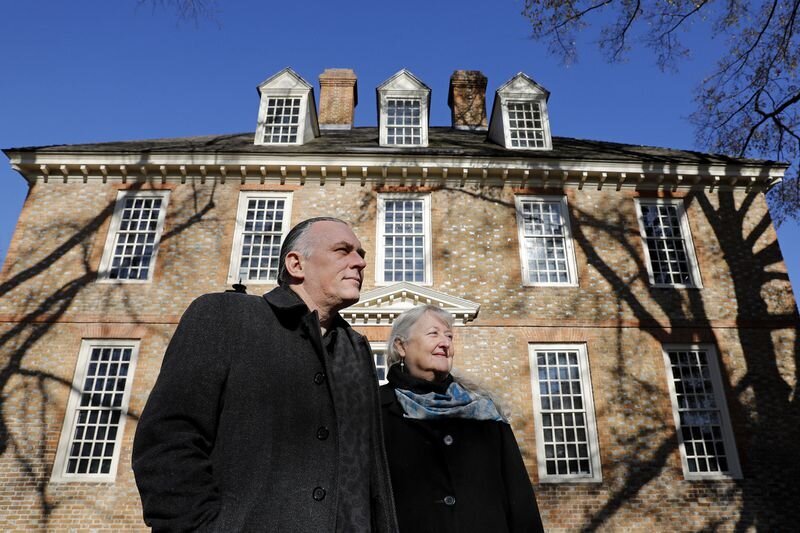

“We used to be there”: The lost history and legacy of America’s Indian School

Buck Woodward, left, American University professor and graduate Ph.D. Historical Anthropology from College of William & Mary and Danielle Moretti-Langholtz, research assistant professor of anthropology and Director of the American Indian Resource Center, stand in front of the Brafferton Building on the campus of William & Mary Friday December 20, 2019. Woodward and Moretti-Langholtz co-wrote the book "Building the Brafferton: The Founding, Funding, and Legacy of America’s Indian School" based on their research. (Jonathon Gruenke / Daily Press)

Several years ago as debate raged over whether two feathers stuck in the College of William & Mary logo was racist, anthropologist Danielle Moretti-Langholtz began getting phone calls from tribes out West.

But the callers weren’t asking about the logo — they were asking about the Indian school that hasn’t existed at the college for more than 200 years.

“We used to be there,” the callers said. “Can we come back?”

For Moretti-Langhholtz, director of the college’s American Indian Resource Center, the requests were puzzling. The Brafferton Indian School stopped taking students in 1779. Today, even the institutional memory of that school is murky. The building is still there. There’s a marker.

She was compelled to learn more.

“Everything I found about the school’s history was very, very minimal,” she said. “Basically, here’s when it opened, here’s when it closed, it wasn’t very successful — whatever that means. And I thought there’s clearly memory in indigenous lands that’s quite different.”

So Moretti-Langholtz and Buck Woodard, then director of the American Indian Initiative at Colonial Williamsburg, set out on a painstaking odyssey over more than a decade to flesh out the complex story of the Indian school, the Native boys who attended — some more willingly than others — and what became of them.

Read the Full Story Here -THEN- Read about our Campus Ministry at a Former Indian School

FINALLY- Did you know: Laws allowing U.S government to force Native American children into boarding schools are still in force?

In Indian Country, a Crisis of Missing Women. And a New One When They’re Found.

Ashley, right, trying to wake up her sister Dani in the motel room where their family is living in Gallup, N.M. Dani had previously been missing for two years, one of many Native American women to disappear in what activists call a long-ignored crisis.

Prudence Jones had spent two years handing out “Missing” fliers and searching homeless camps and underpasses for her 28-year-old daughter when she got the call she had been praying for: Dani had been found. She was in a New Mexico jail, but she was alive.

It seemed like a happy ending to the story of one of thousands of Native American women and girls who are reported missing every year in what Indigenous activists call a long-ignored crisis. Strangers following Dani’s case on social media cheered the news this past July: “Wonderful!” “Thank you God!” “Finally, some good news.”

But as Ms. Jones visited Dani in jail, saw the fresh scars on her body and tried to comprehend the physical and spiritual toll of two years on the streets, her family, which is Navajo, started to grapple with a painful and lonely epilogue to its missing-persons saga.

“There’s nothing for what comes after,” said Ms. Jones, 48, who has five daughters. “How do you heal? How do you put your family back together? The one thing I’ve found is there’s no support.”

Read the Full Story Here -THEN- Learn About the Work We Do to Help Navigate Through Trauma

FINALLY- For further reading: 'Nobody saw me': why are so many Native American women and girls trafficked?

Today’s History Lesson:

This Man was the United States’ First and Only Native American Vice President

After a turbulent childhood in which he survived raids on his land by the rival Cheyenne tribe and his parents’ divorce, Curtis flourished in school and sought higher education with the support of his grandmothers. Given the era and his relative isolation in Kansas, Curtis did not attend law school but rather “read law,” which typically involved an extended apprenticeship, at an established firm in Kansas and was admitted to the Kansas bar in 1881. Before embarking on his political career, Curtis served as a prosecutor for Shawnee County in Kansas.

It’s hard to fit all the news in a little space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!